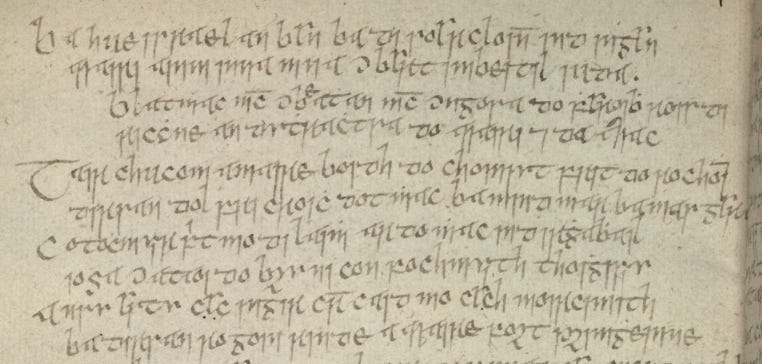

Some time in the early 1950s, a scholar by the name of Nessa Ní Shéaghdha made an extraordinary discovery in the National Library of Ireland. In a seventeenth-century paper manuscript she found two long poems ascribed to ‘Blathmac son of Cú Brettan son of Congus of the Fir Rois’. It soon became clear that these poems were almost a millennium older than the manuscript in which they were contained. Cú Brettan, the poet’s father, was identified as a king in the area now known as County Louth, who died, according to the Annals of Ulster, in 740 AD. The language of the poems – Classical Old Irish – fits this chronology well.

Blathmac himself is otherwise utterly unknown, and these copies of his poems are unique survivals; like the Beowulf poem, they would have been lost if this one fragile manuscript, NLI MS G 50, had not made it to modernity. The poems were edited and translated in 1964 by James Carney, and have been recently re-edited and translated in Siobhán Barrett’s 2017 PhD thesis (I follow her text below, except for a few tiny changes).

Both poems are addressed to the Virgin Mary, and they concern her son: his birth, his ministry, his death, his resurrection, and his return in glory. All of these great mysteries are treated with great care for orthodoxy – ‘this is no heretical tale’ (l. 745) – and in language that ranges from the intimate to the heroic. Mary is the poet’s conversation partner throughout:

I call you with true words,

Mary, beautiful queen,

so that we, you and I, may hold conversation [cobrae] together

to pity your dear one (ll. 573-576).

Blathmac desires not only to talk with Mary, but to weep with her, and he wants such weeping to be ‘heartfelt’ (‘incride’; l. 578). Together, poet and mother contemplate the events of the son’s course, the poet’s compassion increasing by proximity to the mother’s perspective:

Come to me, tender Mary [tair cucum, a Maire boíd],

for the lamenting [coíniud] with you of your very dear one.

Woe is the going to the cross of your son,

he was a great emblem, he was a fine hero.

That I may beat along with you my two hands

over the capture of your fair son (ll. 1-6).

What follows this opening invocation is a detailed meditation on Christ in all his mysteries, with great emphasis on the generosity of Mary’s son, his innocence, and his beauty. Even as a child, we read, ‘he was more beautiful, more pleasant, bigger than other boys’. Blathmac repeatedly underlines the universal benevolence of Jesus:

He called to himself a stout band of people

whose warrior qualities were renowned.

Twelve apostles to whom he was abbot,

seventy two disciples.

Thereafter he began bright gleaming hospitality,

he was prosperous, he was good in lordship.

He used to preach to everyone his benefit,

he used to heal fully every ailment.

He kindled faith in every meadow land

which was fertile, which was inhabited.

He was a sea of springtide of kingship

to whom many thousands used to flock

He used to go about for the good of all,

he was affable, gentle in manner.

In the face of any affliction he did not inflict

satirising rejection or refusal of hospitality (ll. 105-120).

In his suffering this open-hearted charity becomes most vivid: on the cross he was ‘the champion of every person of the host of men and women’ (ll. 497-498), ‘the good shepherd… who has sold himself to the cross for his beautiful flock’ (ll. 826-829), ‘the bright fair lamb… who by his blood has taken away the sins of the whole world’ (ll. 830-832).

The benevolence of Jesus is not limited to humanity, of course. Blathmac understands that, as creator, with the Father and the Spirit, the Son Incarnate is intimately associated with all levels of creation:

This is my clear revelation:

your son is king of the heavens,

his is the sun whose garment is bright,

his is the shining moon.

He owns the extent that he marks out

of the seven heavens around God’s abode.

It is his hand that has arranged in them

the gaming board [fidchell] of beautiful constellations.

His is the earth to his will,

it is he who moves the sea.

He has endowed each of the two,

plants and sea-creatures.

He is the most lordly there is,

he is a hospitaller by virtue of possessions,

his is every flock that he sees,

his the wild beasts and the tame.

It is your son, whose fame is fair,

that owns every bird that spreads wings.

On wood, on land, on clear pool,

it is he who gives them joy (ll. 761-780).

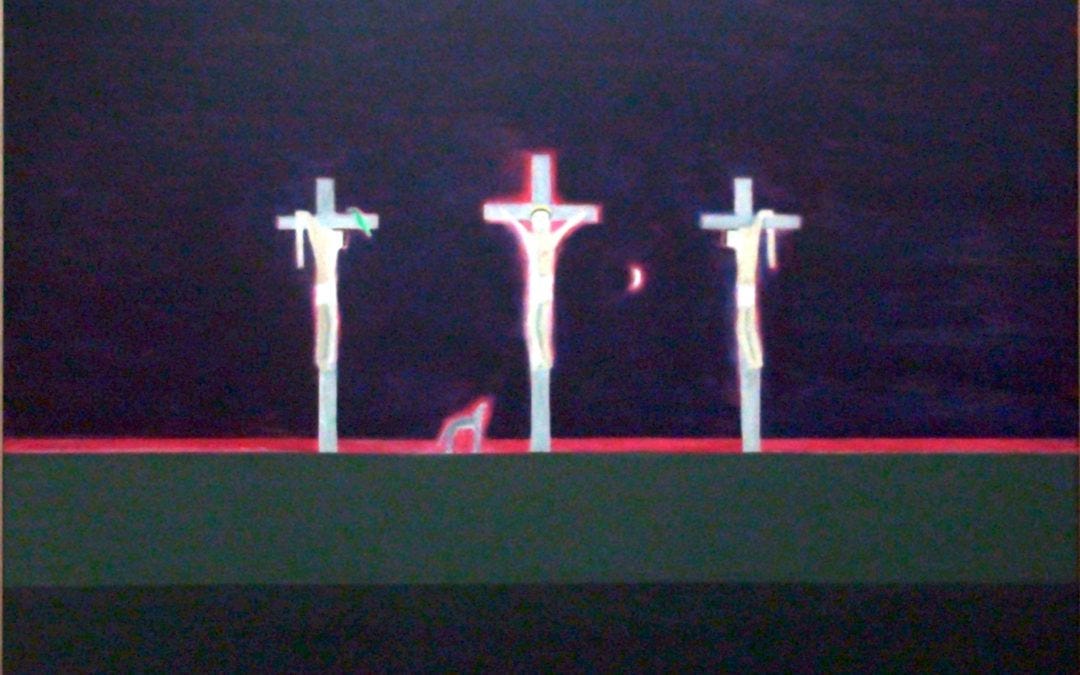

With all these cosmic connections in mind, Blathmac associates the created elements with his own act of mourning. At the crucifixion of Jesus:

The sun hid its own light, it lamented its lord,

a sudden darkness went across the blue sky,

the great tempestuous ocean roared.

The whole world became dark,

the land shook under gloom.

At the death of noble Jesus

great rocks broke asunder.

[…]

A stream of blood gushed forth – too severe –

so that the bark of every tree became red.

There was gore on surfaces of the world,

in the treetops of every chief forest. It was fitting for God’s elements,

beautiful sea, blue sky, this earth,

that they should change their aspect

when lamenting their hero (ll. 241-248, 257-260).

Domestic animals, wild beasts, birds

have pitied the son of the living God,

and every beast that the ocean covers,

has mourned his wounding (ll. 513-516).

Blathmac is taking his cue from Matthew 27, of course, but he extends the image outward to the whole of creation. Likewise, he seeks to extend to his readers his own ‘conversation’ with Mary, drawing others into this nexus of compassion by means of the recitation of the poetic text:

Everyone for whom this [poem] is a vigil-prayer

at lying down and at rising,

for unblemished protection in the next world

like a breast-plate with helmet,

everyone, of every shape, who recites it,

fasting on Friday night, provided that it be with tears without fail,

Mary, may he not be destined for Hell (ll. 557-564).

‘Tears without fail’: this emotional response is clearly what Blathmac is aiming at in his poetry, and his poetic purpose has a theological underpinning. In the wake of the crucifixion, and until the renewal of creation, tears are an essential part of the spiritual life:

It would be natural that there should be until doom

upon every cheek at every single hour

a heavy tear of blood with a mouthful of gore,

lamenting the captive.

Alas the one who has come to love the son of the King of Heaven,

who has seen him lying in gore.

Even everyone who merely heard his fame,

it is incumbent upon them to lament him perpetually (ll. 525-532).

If I ruled as far as every sea,

people of the world according to dignity of wealth,

they would come with me and with you

so that they could lament your royal son.

For the beating of hands without joy,

with women, children, men,

that they might lament on every hill-top

the King who has created each single constellation (ll. 581-588).

Now, medievalists who have read this far might be tempted to scroll back up to double-check the date of the poem. A ‘planctus Mariae’ in the eighth century? A ‘Stabat Mater’, bien avant la lettre? All this ‘affective piety’ and compassionate focus on the sufferings of Christ, long before the supposed spiritual revolution of the twelfth century? This poem simply does not fit the standard chronology of the history of spiritual practices in the West, which makes its survival all the more valuable. It raises many fascinating questions, and it really deserves to be better known.

What about its contemporary reception? Did many in Blathmac’s time make his mournful words their own, weeping in the company of Mary? We simply don’t know, but its single surviving copy suggests that it wasn’t a bestseller. For my part, I read his poems every Holy Week. If you celebrate this sacred season, I hope Blathmac’s poems are a blessing to you too.

This is absolutely fascinating. It has earlier echose of pantheism, and I am reminded of Joseph Mary Plunkett's 'I See His Blood Upon The Rose'. I follow the work of Paul Kingsnorth at the Abbey of Misrule, he is Orthodox Christian but also very interested in the environment, I'm sure he'd love this.